Recycling Vision

Wouldn’t it be great if we took things that we had used and shipped them off somewhere for specialists to process and send back to us for reuse? To this you might say, “Um, yes, that would be called the genius, human-generated idea of recycling.” And to you, I reply, “Of course I know this is already a thing. I just brought it up to snarkily point out that nature came up with it first.” If there’s a good idea, you can bet nature had it before we did.

While society’s recycling programs can make such useful things as plastic water bottles and refurbished phones, our bodies use recycling to make photopigments. If you think you’d rather have a refurbished phone than a photopigment (whatever the heck that is), let me step back and explain that photopigments are the chemicals in your eye that allow an outside signal (light) to enter your nervous system. Put another way, they act as translators, moving messages from the physical language of light into the chemical and electrical language spoken by your brain. No photopigments means your eyes won’t be letting your brain read the texts on your refurbished phone any time soon.

So where are these photopigments, why do we have to recycle them, and where exactly is the recycling facility that’s tasked with this chore? The back wall of your eyeball is lined by the retina, a sheet of specialized cells. One of the cell types found there is the photoreceptor. The light receiver. These cells are full of photopigment. The pigment receives the light message and passes it along to the neural network. The thing is, like many pigmented items (clothing, colored paper, surfers’ hair), photopigments get bleached when light hits them. Now I said that this was the “thing,” but it is not the “problem.” It’s actually useful for the photopigment to get bleached, because that’s what allows it to translate the message. However, once one gets bleached, it’s out of commission until it makes a trip to the recycling facility to get reset.

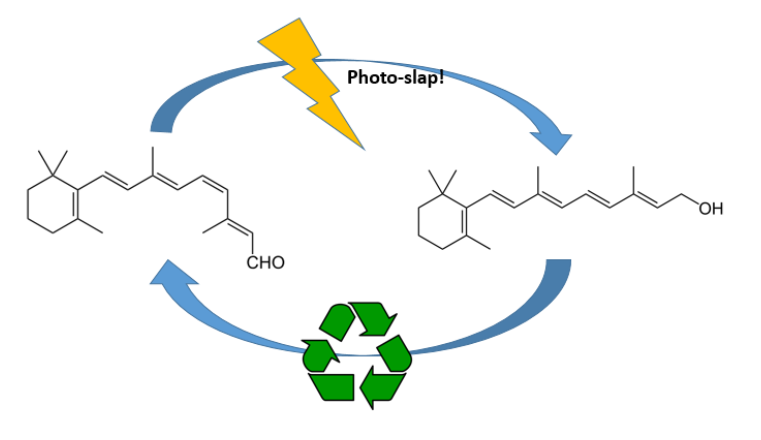

One part of the photopigment is vitamin A. When the vitamin A in the photopigment gets hit by a photon, the tail end of the molecule gets slapped over to face the other direction, as shown above. To be used again, the molecule needs to make a trip to the recycling facility and get its bonds straightened out.

If we didn’t recycle photopigments, after their first use they would just be sitting in the photoreceptor, taking up space, unable to send any signals ever again. We would get one photon of info from each of them, and then our days of vision would be over. Luckily, used photopigments get shipped off to two other cell types in the retina (called RPEs and Müller cells, but here we’ll just call them recycling facilities). When light strikes the photopigment, it changes the direction one of the bonds is facing in the molecule. I like to imagine this as the pigment getting slapped across the face so hard that its head gets stuck to the side. The enzymes in the recycling facility give it some chiropractic work to get its head facing the right direction again, and then they send it back to the photoreceptor. This cycle is running in your eyes all the time as long as there is light, so you always have some photopigments locked and loaded to tell you what’s happening in the outside world.

Next time you pat yourself on the back for tossing your plastic water bottle into recycling, pat your eyes on the back for recycling your ability to see.

BUT-- no recycling program is perfect. I often wonder whether the things I recycle ever actually make it to the facility, and what exactly becomes of them once they get there. These are legitimate concerns for photopigments as well, and that’s where dietary vitamin A comes in. Vitamin A can actually describe a group of compounds, one of which is called retinal. This sounds kind of like retina, and that’s no coincidence. Retinal gets bound to a protein and, ta-da, it becomes a photopigment, hanging out in your retina, letting you see.

We, like other animals, store vitamin A in our livers. As long as you’re eating a reasonably well-balanced diet, you should have plenty on hand when you need some to supplement what you’re getting back from your less-than-100%-efficient recycling facility. If you’re vitamin A deficient, you could possibly get night blindness (exactly what it sounds like: you can’t see at night, when light is rather dim). Since we’re talking about vitamin A being stored in the liver, and we’re playing with “what if’s,” let’s take it one step further. If you were an Egyptian with night blindness around 1550 BCE, your doctor might squeeze the juices from grilled lamb liver into your eyes. Gross, but not illogical. If you don’t believe me on that one, take a gander at the ancient medical text Ebers Papyrus.

While the concept of how our eyes recycle our ability to see is in many ways analogous to recycling a plastic bottle, many details of the cycle have yet to be elucidated. For example, there is a protein that works to speed up the photopigment recycling process, making our eyes better suited to handle a wide range of brightness. Some exciting research in this field is coming out of a lab at Washington University in St. Louis, and I highly recommend you check out (Xue, Y. et al. CRALBP supports the mammalian retinal visual cycle and cone vision. J. Clin. Invest. 125, (2015).). I also recommend you don’t squeeze lamb liver juices into your eyes, but instead see your doctor if you have concerns about your night vision. And with that good advice, I will see you next time!